Flag of the Bahamas

| |

| Use | National flag |

|---|---|

| Proportion | 1:2 |

| Adopted | July 10, 1973 |

| Design | A horizontal triband of aquamarine (top and bottom) and gold with the black chevron aligned to the hoist-side. |

| Designed by | Hervis Bain[1][2] |

| |

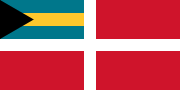

| Use | Civil ensign |

| Proportion | 1:2 |

| Design | A white cross on a red field, the national flag in the canton |

| |

| Use | State ensign |

| Proportion | 1:2 |

| Design | A blue cross on a white field, the national flag in the canton |

| |

| Use | Naval ensign |

| Proportion | 1:2 |

| Design | A red cross on a white field, the national flag in the canton |

The national flag of the Commonwealth of The Bahamas consists of a black triangle situated at the hoist with three horizontal bands: aquamarine, gold and aquamarine. Adopted in 1973 to replace the British Blue Ensign defaced with the emblem of the Crown Colony of the Bahama Islands, it has been the flag of the Bahamas since the country gained independence that year. The design of the present flag incorporated the elements of various submissions made in a national contest for a new flag prior to independence.

History

[edit]The Bahamas became a crown colony of the United Kingdom within its colonial empire in 1717.[3] Under colonial rule, the Bahama Islands used the British Blue Ensign and defaced it with the emblem of the territory. This was inspired by the ousting of the pirates, and consisted of a scene depicting a British ship chasing two pirate ships out at the high seas encircled by the motto "Expulsis piratis restituta commercia" ("Pirates expelled, commerce restored"). The emblem was designed in around 1850, but did not receive official approval until 1964.[4]

The Bahama Islands were granted internal autonomy in 1964.[3] After the 1972 elections, the territory started negotiations on independence.[3][5] A search for a national flag began soon after, with a contest being held to determine the new design. Instead of choosing a single winning design, it was decided that the new flag was to be an amalgamation of the elements from various submissions.[4] It was first hoisted at midnight on 10 July 1973, the day the Bahamas became an independent country.[4][6] The new country also changed its name from the Bahama Islands to the Bahamas upon independence.[7]

Design

[edit]The colours of the flag carry cultural, political, and regional meanings. The gold alludes the shining sun – as well as other key land-based natural resources[4] – while the aquamarine epitomises the water surrounding the country. The black symbolises the "strength",[4][8][unreliable source?] "vigour, and force" of the Bahamian people, while the directed triangle evokes their "enterprising and determined" nature to cultivate the abundant natural resources on the land and in the sea.[9]

Colours

[edit]| Colour | Pantone | RGB | Hexadecimal | CMYK |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aquamarine | 3145 | 0, 169, 206[10] | #00778B[10] | 30, 0, 24, 100[10] |

| Yellow | 123 | 255, 199, 44[11] | #FFC72C[11] | 0, 16, 89, 0[11] |

| Black | None | 0, 0, 0 | #000000 | 0, 0, 0, 100 |

Construction Sheet

[edit]Legal issues

[edit]

The Bahamian flag is often used as a flag of convenience by foreign-owned merchant vessels. Under the Law on Merchant Shipping Act 1976 (amended in 1982), any domestic or foreign vessel – regardless of country of origin or place of registration – can be registered in the Bahamas "without difficulty".[12] Furthermore, the ship's crew is not restricted by nationality and "ordinary crew members" have "virtually no requirements for qualification".[12] This lack of regulation has led to ships flying flags of convenience – like the Bahamas' flag – having a reputation of possessing a "poor safety record".[13] This came to light in November 2002, when the Greek oil tanker MV Prestige flying the flag of the Bahamas split into two and sank in the Atlantic Ocean off the north-western Spanish coast. This produced an oil slick of 60,000 tons of petroleum.[14]

Historical flags

[edit]| Flag | Duration | Use | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1869–1904 | Flag of the Crown Colony of the Bahama Islands | A British Blue Ensign defaced with the emblem of the crown colony. This consisted of a British ship chasing two pirate ships out at the high seas and the motto "Expulsis piratis restituta commercia" (Pirates expelled, commerce restored). |

|

1869–1904 | Civil Ensign of the Crown Colony of the Bahama Islands | A British Red Ensign defaced with the emblem of the crown colony. This consisted of a British ship chasing two pirate ships out at the high seas and the motto "Expulsis piratis restituta commercia" (Pirates expelled, commerce restored). |

|

1904–1923 | Flag of the Crown Colony of the Bahama Islands | The crown on the crest was changed to a domed Tudor crown. |

|

1904–1923 | Civil Ensign of the Crown Colony of the Bahama Islands | The crown on the crest was changed to a domed Tudor crown. |

|

1923–1953 | Flag of the Crown Colony of the Bahama Islands | The crown on the crest was changed to a Tudor crown. |

|

1923–1953 | Civil Ensign of the Crown Colony of the Bahama Islands | The crown on the crest was changed to a Tudor crown. |

|

1953–1964 | Flag of the Crown Colony of the Bahama Islands | A British Blue Ensign defaced with the emblem of the crown colony featuring a St Edward's crown for the new monarch. |

|

1953–1964 | Civil Ensign of the Crown Colony of the Bahama Islands | A British Red Ensign defaced with the emblem of the crown colony featuring a St Edward's crown for the new monarch. |

|

1964–1973 | Flag of the Crown Colony of the Bahama Islands | A British Blue Ensign defaced with the emblem of the crown colony featuring a St Edward's crown. |

|

1964–1973 | Civil Ensign of the Crown Colony of the Bahama Islands | A British Red Ensign defaced with the emblem of the crown colony featuring a St Edward's crown. |

Maritime flags

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Dr Bain Joins The Fabulous Forty". Tribune 242. 2013-06-13. Archived from the original on 2019-07-31. Retrieved 2015-03-15.

- ^ "Our national flag, a mystery of true national pride". Freeport News. Archived from the original on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2015-03-15.

- ^ a b c "Bahamas profile". BBC News. BBC. Archived from the original on June 28, 2014. Retrieved July 2, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Smith, Whitney (October 6, 2013). "Flag of the Bahamas". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved July 2, 2014. (subscription required)

- ^ "History of The Bahamas". Lonely Planet. Archived from the original on May 27, 2017. Retrieved July 2, 2014.

- ^ McJunkins, James (July 10, 1973). "New Flag Hoisted Over Bahamas". The Palm Beach Post. p. A1. Retrieved July 2, 2014.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Albury, E. Paul (October 7, 2013). "The Bahamas – Independence". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved July 2, 2014. (subscription required)

- ^ "Your Trip to Bermuda: The Complete Guide". Archived from the original on 2017-08-09. Retrieved 2017-08-09.

- ^ "Bahamas, The". The World Factbook. CIA. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved July 2, 2014.

- ^ a b c "PANTONE® 3145 C". Archived from the original on 2021-07-14. Retrieved 2020-11-16.

- ^ a b c "PANTONE® 123 C". Archived from the original on 2016-03-09. Retrieved 2020-11-16.

- ^ a b Egiyan, G.S. (March 1990). "'Flag of convenience' or 'open registration' of ships". Marine Policy. 14 (2): 106–111. Bibcode:1990MarPo..14..106E. doi:10.1016/0308-597x(90)90095-9. (registration required)

- ^ Kelly, Nicki (May 11, 1983). "Bahamas becomes newest ship registration center". The Christian Science Monitor. Boston. p. 10. ProQuest 511963314. Archived from the original on December 22, 2017. Retrieved July 2, 2014.(subscription required)

- ^ Ordás, M. C.; Albaigés, J.; Bayona, J. M.; Ordás, A.; Figueras, A. (2007). "Assessment of In Vivo Effects of the Prestige Fuel Oil Spill on the Mediterranean Mussel Immune System". Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. 52 (2): 200–206. Bibcode:2007ArECT..52..200O. doi:10.1007/s00244-006-0058-7. PMID 17180482. S2CID 1108017. (registration required)